How do you make decisions? Most of us don’t even think about it. Literally. Our subconscious mind takes over most of the time as soon as we are faced with a problem. When we do think about it consciously, some of us make choices based on feelings and others do it based on their rational thoughts. Likewise, some of us have a narrow approach, where others try and look for all the perspectives possible. Thinking and making decisions is done differently in all parts of the world. It’s how we are raised and how society works. In this piece, I would like to introduce you to certain international ideas on how to approach decision-making.

The first example of this is Kate Ransworth. She argues that we need to change our choices in our economy to more conscious ones. She developed The Donut Theory, in which she states that we need to make choices for our economy within our limits of social and ecological development. If we don’t do this and we keep putting economic development first, the consequence will be an ever-growing footprint and more poverty worldwide.

Another interesting integral theory is ‘Dragon Dreaming’. Dragon Dreaming is a participative, holistic, and highly structured method to realize creative, collaborative, and sustainable projects. It is based upon the principles of personal and group empowerment, win-win, consensus, and commitment. It was designed in Australia by Vivienne Elanta and John Croft, with wisdom from the Aboriginals and other indigenous people as a baseline. They linked this way of thinking and living to Western actions. In this way, a project process was created in which there is as much room for managing and monitoring as there is for visualizing and celebrating.

From Kinyarwanda (the language spoken in Rwanda), there is the word ‘Ubumuntu’, which means “to be human.” To genuinely care about others, to be generous and kind, to show empathy, to be sympathetic to the plight of others, and to recognize the humanity of others. An inspiring and hopeful concept for a country that has suffered much pain from the Genocide in 1994. It focuses on the other and not on yourself.

Based on the South African concept of Ubuntu (I am because we are), “Lekgotla” is an interesting approach to decision-making. Lekgotla is a public assembly, community council, or traditional court of a village in Botswana. It is run by the village chief or village leader. Decisions of the community are always made by consensus. No one is allowed to interrupt another while expressing their opinion. This is applied to all kinds of different issues.

But, as far as I’m concerned, we even need to take a step further than the concepts above. We should not only look at the balance between different subjects or people’s input and emotions, but we should become aware of our own perspective when we make a decision.

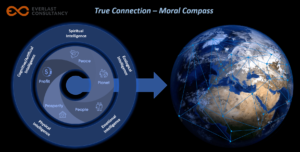

Nowadays, we are told decisions should primarily be made rationally. We are even working on getting computers to make decisions for us. But if we look at the world and the problems that exist in the social and ecological field, we need a new assessment framework: a new moral compass that guides us to good decision-making. That new moral compass requires more than just cognitive and artificial intelligence with a piece of pre-programmed morality.

To many of us, it is unknown that we actually possess six different ways of intelligence. That makes sense because nowadays, we only use some of them. In the time of the first humans we mainly needed ecological intelligence, because we needed food from nature to survive, we needed to understand nature and be one with nature. We also needed physical intelligence to stay strong to hunt and catch bushmeat. You had to understand your body because doctors did not exist yet.

We noticed that we needed social skills to live with others as well, so we developed emotional intelligence. When we started asking ourselves more questions about how the world worked and we had trouble answering them, we started looking for spiritual intelligence, a handhold from the unknown. Slowly but surely we started to understand things because we started to understand the world more and technology developed that helped us do that. In this way, we developed our cognitive intelligence.

In the meantime, we have drifted away from our ecological, physical, emotional, and spiritual intelligence and we do not see the value of these intelligences enough to take them into account in our process of decision-making. We are relying on our cognitive intelligence, with the result that we are now striving for prosperity instead of well-being.

So, I think we need a new moral compass that will help us strike a better balance in the use of our different intelligences.

Yet there are plenty of wonderful examples we can learn from when it comes to applying multiple intelligences. I once visited an indigenous Indian tribe in the Amazon forest of Peru. After a major flood due to climate change, most of the bushmeat had been killed. The indigenous people deliberately waited several years before hunting until the ‘level’ bushmeat was back to normal. They understand that they must strive for sustainable consumption and also respect nature.

Another example is a trip I took to Vietnam and on one of the islands there I met a man who worked in the hotel where I was staying. Despite the fact that he worked 7 days a week in the hotel and evenings in a restaurant and only had 5 days off a year, he wanted to show me around the island on his scooter for a day, sacrificing one of his scarce free days. He wanted nothing for it and stated that from his Buddhist attitude if he makes someone else happy, he himself becomes happy. A consideration that was not made purely on cognitive grounds.

Once in South Africa, I paid a visit to a white woman who told me about the black population and how criminal they are and that she had been robbed. When I left, I was shocked and thought I had spoken to a racist. In South Africa, there is a lot of criminal behavior among the black population. Later I realized that she is not a racist, but just very scared. In addition, you should not label the black population as criminals, but understand that they are also afraid of whether they can gather enough food every day. So the problem is not racism or criminal behavior, but the underlying problem of inequality in South Africa. If you had only addressed this cognitively and left out the emotional side, you would be making the wrong choices in finding the solution.

This is not to say that it is easy to make decisions from multiple intelligences, but it is necessary. A good example is the idea of building a new highway from Lake Victoria to Mombasa in Kenya. This would allow the fish caught in the lake to be transported much faster to the port city and make much more money for the poor people in Kenya. However, the herds of wildebeest, as well as zebra and gazelle, migrate through the Serengeti in Tanzania to the Masai Mara in Kenya and back again. On the route are a number of obstacles, such as the famous Mara River in Kenya. A major highway would cause this migration to be disrupted, which would mean an immense decrease in the number of wildebeests, resulting in a decrease in lions and other wildlife that use the wildebeests and gazelles as food. People in Europe, in particular, thought this was a bad idea because of the tourism surrounding this wildebeest migration. The President of Kenya stated: you Western rich people are worried about a nice wildlife picture, while in Kenya people are starving to death. The key point is that you have to weigh multiple sentiments carefully.

But how do you get a better balance in applying your intelligence? Sustainable development goals can guide us through that process. Linking the SDGs to various intelligences gives us insights into the contribution of the SDGs and the parent Ps (people, planet, profit, prosperity, peace). However, if we really want to see results, we need more than a technocratic approach. Sustainable solutions for whichever problem we face, come from the combination of intelligences. The results? A new balance in economic, social, and ecological preservations and better development of humanity and the world.

What I hope is that you can start to rediscover all of your intelligences. Listen to your gut feeling more often, and sharpen your eyes and ears to find more ways to approach any obstacle or problem you face. That way, we can collectively build a new world.

0 Comments